How female scientists in Seattle are part of a global movement to create a just, equitable, and science-informed world

Sarah Myhre will be reading at Cascadia Magazine’s Evening of Words + Ideas at the Rendezvous Jewlebox Theater at 7 pm, Friday Sept. 13. More details here.

In the last year, in this acute political moment we are all surviving, many people have asked me, “Why women, why science, why now?”

I have an answer to that question. But, it might not be the answer you think it is. Is it about upholding the rightful place of science in public life? Absolutely. Is it about women’s rights? Definitely. Is it about protecting our democratic and scientific institutions from the terrifying creep of authoritarianism? You betcha.

But, it is also about the grief and consequence of white privilege and supremacy. It is about the crushing weight of surviving inside institutions that were never built for you or your body. It is about realizing you have been self-silencing, gaslighting, and compartmentalizing your own experiences in the world, because if you didn’t you would crumble from the wounds you’ve endured. It is about saying no in public, maybe for the very first time.

Inside of institutions such as science, academia, business, and even marriage, the culture tells women, “Be small, be docile, be quiet, and you will be rewarded.” This is not true. This is a lie. There is no reward inside a system that requires docility. There is only subjugation.

When the United States elected a man to its highest public office who bragged about sexually assaulting women, the world changed for women. Trump’s election, if anything, was a catalyst for exposing the ubiquitous costs women pay in their professional and personal lives because of misogyny. Suddenly, those birds of docility came home to roost in a terrifying way. Our subjugation was laid bare.

For women scientists (for our purposes here, I am essentially referring to women in STEM professions and medical practitioners), the election of Trump came with a decided professional cost. When you are an evidence-based practitioner and an anti-evidence administration is elected, the value and use for your work in the world is cheapened, erased, and revoked. This isn’t a casual depreciation. It is a loss of power to the people whose careers should be directly informing public policy, protecting public safety, and reducing public risk.

Personally, I was stunned by the election. Later, as the shock wore off, I examined that reaction. Yes, maybe it made sense for me, a white scientist lady, to be shocked at the power and currency of white nationalistic rhetoric. But, I asked myself, would women of color, who had experienced racialized violence and discrimination, have been shocked by the power of white supremacy? No. And in that moment, my white privilege was laid in front of me like a landscape of ignorance. I was able to see clearly for the first time how I could turn towards—and then turn away from—social justice because of the privilege of my white skin. The election was not only a moment of acute trauma; it was also a profound indictment of my complacency and dehumanizing apathy towards others.

In the election’s aftermath

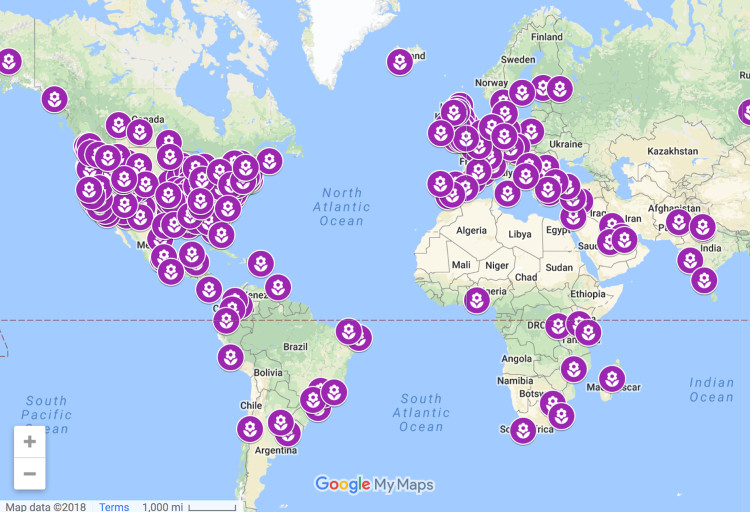

In the immediate nuclear fall-out after the election, women scientists began to form new organizing hubs. Five women scientists (and also graduate school friends), Kelly Ramirez Ph.D., Jane Zelikova Ph.D., Theresa Jedd Ph.D., Teresa Bilinski Ph.D., and Jessica Metcalf Ph.D. drafted an open letter “To and From Female Scientists” articulating how they would stand together to defend a just, equitable, and scientifically-informed world. What began as a group text among grieving friends, with the aspirational hope of finding 500 other women who would sign in solidarity, turned into a global movement of feminist activism and public scholarship. Now, more than twenty thousand women scientists and allies, from over one hundred countries, have signed the pledge. There are local organizing chapters, or pods, of women scientists forming across the globe.

From the success of the open letter and the solidarity in mission between women scientists, a new organization formed. The vision of 500 Women Scientists (full disclosure: I am a founding board member) is to be the leading global organization engaged in the “transformation of leadership, diversity, and public engagement in science.” One of the most powerful tools built by the organization is called Request a Woman Scientist. Women, especially women of color, are invisible within the scientific workforce. This resource for journalists and policy makers, which now includes thousands of women scientists from across the world, is a step towards representation in the public. If you want to change the culture, then first you must be heard and seen by the culture.

Seattle 500 Women Scientists

Here, in the Pacific Northwest, I have founded and help lead the Seattle chapter. We are an approximately 150-member strong regional organizing and activist hub, with a leadership team of ten Seattle women scientists. We are brain scientists, fisheries scientists, and climate scientists. We are women’s health professionals and disease epidemiologists. Over the last year and a half, we have marched for Black Lives Matter, for Womxn, for Science, for our Peoples Climate, and in The March For Our Lives against gun violence. If you’ve been to any Seattle protests since 2016 and seen a bunch of dancing lady scientists in lab coats with cookies and a bullhorn—that was us.

Moreover, we are doing the necessary work of changing the conversation and culture in Seattle. We have organized public talks with regional experts, including scientists such as Sapna Cheryan Ph.D., scientist turned State Representative Vandana Slatter Ph.D., and labor leader Michelle Tigchelaar Ph.D. We have published guest editorials on Integrity and Scientific Reporting on Climate Change and how Puget Sound Energy Needs to Stop Burning Coal in Montana.

We attended in solidarity, grief, and outrage the public memorials for Charleena Lyles. A black mother murdered in her own home by Seattle Police Department. We have issued public statements on DACA and bipartisan immigration reform and the tolerance of Patriot Prayer hate speech on UW campus. Our members register voters, have individually helped to gather signatures for Initiative-940 (De-Escalate Washington – to reduce police violence) and Initiative-1631 (a carbon-fee and climate action initiative). And we recently raised more than $800 for Cienca Puerto Rico – an organization focused on rebuilding scientific and educational infrastructure in Puerto Rico by hosting a science trivia event and public talks.

In short, we are showing up to do the work of public scholarship and to help build a more just, equitable, and science-informed Seattle. We may be late to the table of social justice and equity, but late is better than absent.

Women’s empowerment versus feminist leadership

Many women come to feminism because of acute personal crisis. For some, it could be the election of Trump. For others, it may be due to sexual violence or institutional discrimination. This personal experience of feminism, often interpreted as female empowerment, stands in contrast to a different concept of feminist leadership.

What is feminist leadership? It is leadership that chooses to turn towards the discriminatory, white supremacist, and patriarchal systems around us in order to dismantle them. Unlike the frame of female empowerment, which often reinforces existing hierarchies by telling women to “Lean In,” take charge (like men), and be assertive (like men), feminist leadership and structural thinking questions how we can change institutions that were never meant for us in the first place. Real liberation will not come about by women simply acting like men and being rewarded for it.

I talked with Sapna Cheryan Ph.D., an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Washington, about this schism in feminist thinking. Dr. Cheryan studies women in STEM workplaces, and so she sits at a critical intersection of professional and personal expertise regarding feminist leadership. Dr. Cheryan articulated how this structural approach to feminism “really helps us to see how men are the default and women are considered the other—that there are negative consequences because of this thinking.”

She is currently conducting research on how this masculine default—or the rendering of masculine traits as the optimal or ideal—is a form of bias that occurs on personal and institutional levels with real, negative consequences.

When I talked with Dr. Cheryan, she thoughtfully questioned how feminism might change not only our leadership choices, but also our scientific research. Maybe we don’t want the masculine, risk-taking, lone-wolf version of scientific inquiry to be the cultural default. Maybe that isn’t the best kind of science we can do. Maybe a careful, collaborative, feminist version of science would be better. As we spoke on the phone, I agreed with her.

Afterward, I cataloged how I have been trained as a scientist to broker for power as a man—through argumentation and confrontation. Indeed, as a graduate student, I was told by a famous male scientist that ,“the way to build your career in science is to destroy the careers of others.” If that isn’t toxic masculinity, I don’t know what is.

Building new worlds

For many of us, the question of “why women, why science, why now?” is deeply personal. Yet there are real, glaring structural reasons there has never been a better time for science-informed feminist leadership. Not because of Trump’s election, but rather because of what Trump’s election revealed about our complacency and privilege. Waking up to one’s privilege in the world is only the start of the work. As Dr. Cheryan said to me, “Privilege is not inherently bad—it doesn’t mean that you are a bad person, but it should obligate you to act on behalf of others.” I would absolutely agree.

What could women in science do to change the world to be more just, safe, and prosperous? First, we must recognize our own power, despite having survived inside institutions that were never built for us, within a culture that defaults to and rewards male traits. We must never be docile again. We must turn towards those inequitable institutions and cultures defined by patriarchy and white supremacy, and tear them down to the ground. This isn’t just about women’s liberation, this is also about changing the world so that it is no longer “their world” but “our world.”

We have only just begun.

Sarah E Myhre Ph.D. is a paleoceanographer at the University of Washington and a national thought leader in the field of climate science communication. She is an unapologetic advocate for representative leadership and the importance of women’s rights. She is the founder of Rowan Institute, which is a leadership and communication nonprofit for a hot and dangerous planet.

All images courtesy of Sarah E. Myhre.

If you found this article informative, please consider making a donation today. Cascadia Magazine is a reader-supported publication, and we rely on the generous financial support of readers like you to publish great writing on issues that matter.