Scientists studying marmots in the high meadows of the North Cascades are concerned about their decline

We walk across a bridge over the Stehekin River and soon emerge at a mown field dotted with a couple dozen tents. Some are camo patterned, all are newer, and they’re bordered on one side by a row of porta-potties and outdoor sinks. Quite a lot of support for a carnivore research project, I think.

“Is this us?” I ask.

“That’s the firefighter crew,” Logan tells me. “There’s a fire up on Devore Creek.”

It’s then I see the trucks, beefy pickups with red cabs and flatbeds holding pumps and generators. Logan steers me toward a park service shelter, where a young man in patched jeans is standing barefoot by a picnic table. He extends his hand and introduces himself as Rawley.

Logan Whiles is a graduate research assistant at Washington State University studying predator-prey interactions, and Rawley Davis is his summer field technician. The three of us are about to spend a week in Washington’s North Cascades National Park observing hoary marmots, collecting carnivore scat, and checking on wildlife cameras. This will be Logan’s fifth time making the roughly sixty-mile trek.

There is evidence that hoary marmots are in serious decline in the North Cascades National Park. One hypothesis for the loss suggests that less snow due to a warming climate opens the restaurant doors for carnivores that otherwise dine at lower elevations…

A little later we’re looking at a map when the firefighters return. They walk single file in matching navy shirts and are slightly hunched from their heavy packs. One is carrying a huge chainsaw wrapped in cloth. It’s hot, the sun feels close, and warm gusts rush down the Stehekin Valley, which for millennia was used as a route by Columbia Plateau and coastal Salish tribes for trade, marriages between tribes, hunting, and gathering.

Early the next morning I talk to a firefighter named Kevin. He tells me about the lightning-ignited fire’s behavior, how it drifts with the winds upslope at night then back down during the day. The crew is clearing thirty feet of brush to create a firebreak to protect the tiny town of Stehekin. He heads off to join the others on a bus that will take them to breakfast.

I figure if the fire is a problem he would have said something.

About the size of a big house cat, hoary marmots are in the ground squirrel family. Their mountainside colonies can be hard for researchers to get to, but once you’re there, marmots are relatively easy to observe, often spending hours above ground sunning, chasing, and what Rawley describes as sumo wrestling. Some of their common names include rockchuck and watchman of the crags.

Their subspecies name (caligata) comes from the Latin term for booted, a reference to their charcoal-colored feet. They have a silvery pelage (like hoarfrost) and a bushy brown tail and are found from northern Alaska south through the northern Cascades and Rocky Mountains to southern Montana and Central Idaho.

There is evidence that hoary marmots are in serious decline in the North Cascades National Park. One hypothesis for the loss suggests that less snow due to a warming climate opens the restaurant doors for carnivores that otherwise dine at lower elevations (such as coyotes and bobcats). If more marmots are being eaten by these lower elevation animals, then the rare higher elevation carnivores like wolverines and lynx could be forced into competition. This in turn could throw already stressed habitats further out of sync.

Scientists are still determining to what extent human or carnivore activity in the North Cascades affects hoary marmot behavior. They want to know which carnivores up here are eating marmots. Whiles and his team theorized maybe bear (grizzlies are known to dig marmots out of their burrows), but there are currently no grizzlies here, and last season the team collected enough scat to realize that local black bears chomp more veg than they do meat.

Jocelyn Akins is the conservation director for the Cascade Carnivore Project, a group studying the North Cascades marmot decline in a collaborative effort between Washington State University and the National Park Service. I was curious if Akins thought she was witnessing an extinction event before her own eyes.

“It’s easy to get the cart before the horse,” she said over the phone. “We’re figuring out the complexities of what the decline is, the extent.”

I ask Logan the same question on the trail, and he answers similarly.

“We’re in the knowledge-gathering phase,” he says.

We hike for about an hour when we come upon bear scat. It looks like someone lit an M-80 under a plate of sausages. Red mountain ash berries are peppered among the rubble. Rawley sets down a ruler and begins to take photos.

We pass an unafraid young grouse in a patch of false Solomon’s seal before entering a forest of Western red cedar. Around a bend I hear branches cracking and pause. Before leaving camp Logan asked if I was okay seeing bears.

“Sure,” I said.

“Cool. Is it alright if we leave the bear spray?”

“Sure,” I said, trusting him as I did Kevin.

I take a few cautious steps and see it’s a grazing black-tailed deer, indifferent to my presence. We continue on, stopping at a sunny stretch where Rawley points out a bluebell tiger moth. It works its way up a thick stalk of grass, powder blue patches inlaid in its black heart-shaped wings, orange fur on its cheeks.

Eleven miles later we reach camp. We’re at 4,000 feet of elevation with a clear view of Buckner Mountain, which is split in half by the lumpy back of an enormous rock dragon. The snowfields on either side are like plates in its scales.

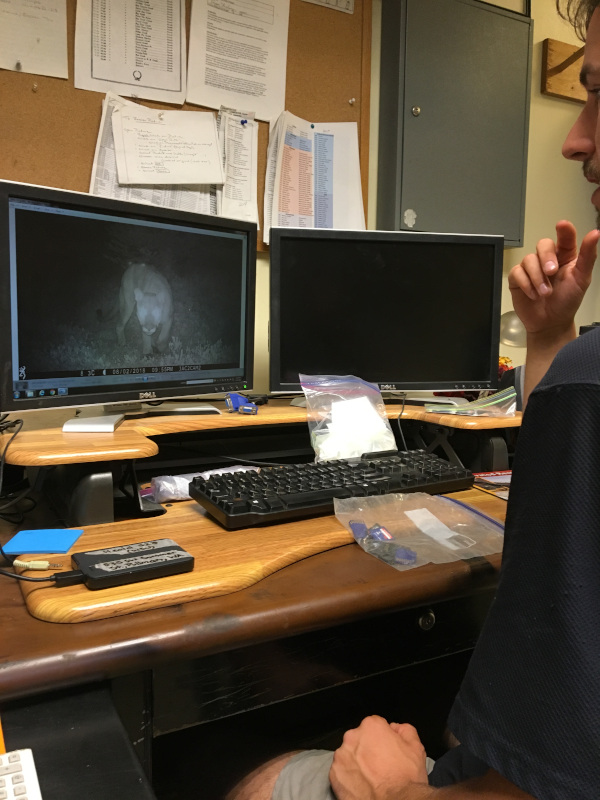

There’s cougar scat near my tent pad. I am surprised that such a large animal frequents the area, but I soon learn carnivores use human trails for the same reasons we do: to easily get from one place to another. Logan later shows me a nightshot of a cougar caught on a wildlife cam. The cougar’s eyes glow like headlights, its bunched shoulder muscles full of power. He pulls up a picture from the same cam of a man hiking, noting the cougar is about waist high.

“Welcome to marmot country,” Logan says.

It’s shortly before 7 a.m. and the trail has turned from dirt to rock. We’re at 5,000 feet elevation and climbing, and the meadows are sprinkled with colorful midsummer wildflowers. Two hoary marmots are whistling back and forth. Logan classifies the tone as an alarm call, one of their seven known vocalizations. The regularity of the pitch and timing, and the way they carry over a big open space, brings to mind foghorns. These unmistakable calls have led to an array of other common nicknames for marmots, including whistler, whistling pig, white whistler, and whistler of the rocks.

The first marmot I see is atop a hippo-sized rock, its head slightly tilted in a pose of curiosity, its bushy tail resting against its rump. The boulder is tucked in a bed of heather, pink aster, and fireweed (marmots are big flower eaters).

The view from our observation rock is stunning, the staghorn peaks of the Glacier Peak Wilderness spread beneath the soft blue morning sky. The glaciers hanging off Booker and Buckner Mountains start to sparkle with the growing light. The sun has not yet climbed over 9,000 foot-high Goode Mountain to our left, and a distinct shadow line cuts the mountainside. In the distance there’s a light plume of smoke from what we figure is the Devore Creek fire.

Logan chooses a marmot to observe. He speaks into his phone while gazing through his binoculars (which the researchers call binos, rhyming with rhinos). He rattles off the action like a sportscaster.

“Foraging,” Logan says, as the marmot sniffs shrubs.

A minute or so passes and it disappears behind a big rock.

“Out of sight.”

I hear a crack and turn to watch a hunk of glacier ice break off a nearby mountain, gathering rubble as it surges downhill.

“Social,” Logan continues when the marmot returns with a pal. It climbs onto a sloped rock, flattens itself and rests its chin on the ridge. “Looking,” he says.

A minute later he says, “still looking.”

“Action has resumed,” Logan says when it gets up to chase a squirrel.

The five behaviors—looking, foraging, social, resting, other—are how Logan classifies his observations. “Other” includes grooming, burrowing, sprinting, and mounting (marmots are quite private: mating has yet to be directly observed by biologists).

“Looks like the sun got the best of him,” Logan says, the marmot basking in the warmth that has just crested the wall.

I ponder what I know about marmots thus far. They get the hiccups. They defecate in the morning. They’re monogamous and polygamous. Two females can share one colony, to take turns breeding while the other rests.

After the observation Logan readies himself for the Flight Initiation Detail. He will drop bandanas like breadcrumbs as he approaches the marmot; one for his starting point, another the moment the marmot looks at him, others for when the marmot bolts and slips into a burrow.

Hoary marmots reuse hibernation burrows for decades, and have refuge burrows scattered about their colonies like escape hatches. Logan scrambles over the rocky ground toward his subject. It soon raises its head and whistles, before vanishing over the side of the rock.

After our observation we head up the trail to check a wildlife cam strapped to a tree. Logan opens the case and pulls an SD card out and attaches it to a device plugged into his phone. He shows me a night shot of a mule deer, its four-point antlers glowing in the dark, the image so vivid I can trace the vein running down the side of the deer’s face.

Yes, he tells me, people mess with the cameras. They’ve been mooned, peed on, flipped off, and even stolen. But the majority of people who notice the cameras smile and wave, read the laminated sign with the Cascade Carnivore Project web address for more information. The researchers have received plenty of inspirational emails sent by folks eager to share wildlife stories.

On the way to Park Creek Pass to check another camera we stop to watch a bear swimming in a tiny lake. It crosses from one side to the other, sits on its butt near shore; it flops in and floats on its back, then suddenly runs out. The bear dashes across a creek, crosses it again where it oxbows, before disappearing over a ridge.

The snowfield melt at the pass has been enough that they need to reposition the camera. Logan jams the stake it’s attached to into a lower pile of rocks. He shows me a picture of a bear traversing the pass in a storm. It’s a lonely image, a thick fog backdrop where I’ve been seeing open sky and jagged peaks. The bear emerges from the fog, its mouth open, its soaked leg fur cowlicked in places. To make sure the camera is repositioned correctly, Rawley hunches over and swings his arms in emulation of a bear passing the lens.

The following morning we break camp early and head down a brushy trail full of cow parsnip, salmonberry, and corn lily. Logan informs me the lily leaves make for good emergency toilet paper.

I spot a young marmot; it’s mostly gray, fuzzier and rounder than the adult. The adult has a dark gray head and lighter back and caramel hindquarters spilling into its tail. I ponder what I know about marmots thus far. They get the hiccups. They defecate in the morning. They’re monogamous and polygamous. Two females can share one colony, to take turns breeding while the other rests. They’ve exhibited “reproductively suppressive” behavior, wherein a female kills the offspring of a “weaker” female. For eight months of the year they are suspended in a state of deep torpor.

I’ve heard about a marmot who tried stealing a man’s tent. A family near the post office in Wenatchee has adopted a family of marmots. The family built a doghouse, and named the pets after Ice Age characters. A woman on the Lake Chelan ferry said marmots in Spokane had overrun the lawn of a riverfront restaurant. People got married there!

Lusty or vicious, wily or cuddly: we see what we want in animals. The marmot strikes me as a comic character with Zen tendencies. It’s playful and curious and likes to gaze; it’s adaptable up to a point. The Vancouver Island marmot is one of Canada’s most endangered animals, and has been pulled back from the brink of extinction (it was down to under 30 individuals in 2003) by a conservation group. Its future is uncertain, and it’s still considered critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

“He’s on the move,” Logan says as his subject hurries off a rock.

A minute later, he adds: “out of sight.”

For the next two days I will not see or talk to another person besides Logan and Rawley. We repeat our observations and collections, filter water and don layers against the black flies, tell stories and contemplate nature. I’m hiking alone on what I’m told is a bear-heavy trail the fourth day when I think I hear children singing. The voices increase in volume, and I recognize the song: “The Ants Go Marching.”

It’s a mom and her two children, and when I tell them I’m with scientists researching marmots the eyes of the kids widen as if I said I’d just spotted Santa.

“They’re my favorite,” the mom says.

Up the trail a little ways I run into the husband and son. I repeat my spiel, eager to chat with someone after so long in the social desert.

“That’s mom’s spirit animal,” the boy says as a matter of fact.

I am touched by their lightness, and of course don’t mention how populations of the whistler of the crags are declining.

During dinner Logan reads a message he received on his emergency transponder. It’s from his parents. The Devore Creek fire has at least doubled. Stehekin is on “be prepared” status.

“It could be old,” he says.

The sky has a pinkish hue in one half and dusky blue in the other. But I don’t smell smoke or see ash, and again defer to his experience. I wake around four a.m. to rain splashing my face. I throw on the fly tarp, and comforted by the natural extinguisher, doze back off.

People have a hard time reconciling the reality of a thrumming meadow with data-driven doom. Logan reminds me the meadow is just a snapshot. It doesn’t mean global warming and mass die offs are not happening.

Rain drizzles the following morning and we get soaked tromping through tunnels of thimbleberry, Sitka alder, and vine maple. We stop to look at bees sleeping under the umbrellas of fireweed flower petals. We duck beneath willow branches to scroll through pictures. There’s a woodrat at night sitting on a rock. There’s a porcupine, also in the dark, its quills like an aura tracing the curve of its back, darker where they thicken above the rump. After an hour or so the sun begins shining through gaps in the clouds and we hear the whistle.

It’s not until I slow down for the observation that I realize the beauty of where we’ve emerged. We are across from the glacier-pasted north faces of Goode and Storm King Mountains. Vaporous clouds sieve through the stegosaurus plates lining Storm King’s crest; the mountainsides are threaded with waterfalls that alternate between horsehair and terraced and stringed. Dark green mountain hemlock and lighter larches climb up into the mist.

Through my binos I watch two young marmots wrestle. They stand on their hindlegs and wrap forepaws around one another’s shoulders and begin to turn slow circles. Their tails whip a million miles an hour. One falls over the edge of the rock and scrambles back up and they start again. The adult sits nearby intent upon staring into space; does it see the wisp of the cedar waxwing’s bright yellow tail when it flies past?

As I walk through a meadow charged by fresh sun—bees and bugs are buzzing among dripping leaves and flowers—I understand one of the key challenges for scientists in an era of quickly shifting environmental winds. People have a hard time reconciling the reality of a thrumming meadow with data-driven doom. Logan reminds me the meadow is just a snapshot. It doesn’t mean global warming and mass die offs are not happening.

Indeed, earlier this year a U.N.-backed group of over 300 international scientists issued a gloomy assessment of biodiversity loss. Writing about the findings, Elizabeth Kolbert summarizes: “On the order of a million species are now facing extinction, ‘many within decades.'” While habitat destruction is a main driver of species loss, climate change is emerging as an accelerator.

Logan notes that it’s hard for people to trust not just science, but scientists. They are mysterious characters fiddling with camera boxes, recording play-by-plays of big squirrels, sticking weasel poo in vials. They speak in Latin and jargon. It doesn’t help that the rise of fake news and alternative facts pollutes the ground of truth on which they stand. Disinformation campaigns fueled by emotional rhetoric box them into a politicized corner, and they are increasingly having to confront the ways in which they communicate their work.

What they are doing is gathering knowledge in a vast lab we smartly set aside as parkland fifty years ago. The marmot whistling and glacier glowing, the bluebell tiger moth climbing the stalk, the northwest dragon lizard scuttling through ankle-high brush. The western tanager flicking past looking like a goldfinch with a scarlet ski mask, or Pacific fir weeping clear sap—this is the genetic diversity future scientists will study. How rich and diverse an ecological mosaic we leave future generations largely depends on how seriously we take their current warnings.

Photo credits: marmot in a boulder field, marmot in snow, and wildlife cam of black bear by Cascades Carnivore Project. Marmot perched on a rock by Kevin Cortes. All other photos by Paul Lask.

Paul Lask is a writing instructor and adjunct faculty at Oregon Coast Community College. His feature for Cascadia Magazine, Coring the Forest, was awarded a first place award in the Health & Science category (small publications) from the Western Washington Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists in 2019. He’s also published work in Willamette Week, Travel Oregon, and Fail Better magazine.

If you appreciate Cascadia Magazine’s award-winning environmental reporting, please make a contribution to our Fall Fund Drive. We can’t continue to publish articles like this without the support of readers like you. Find out more at our donate page.