Is non-monogamy becoming the new normal across Cascadia?

Brittany and Scott live in a cookie-cutter development on a hill above a small city north of Seattle. It’s the kind of suburban neighborhood that triggers both repulsion and envy in me. I assume the people who live here don’t share my liberal politics. But when I see the toys, small bicycles, and people working in their front yards, I recognize the neighborhood for what it is; a vibrant community filled with families, the kind of place I’d probably enjoy living with my own kids.

But I feel out of place here. I’ve come to ask questions that I assume would, at the very least, make these people feel uncomfortable, if not hostile. I am accustomed to the urban vibe of cities, places at ease with the ‘I’m ok, you’re ok’ attitude. This suburban neighborhood feels as though I ought to conform. Brittany and Scott appear to fit right in. On the surface at least.

Both their front door and back, if not open, are often unlocked, and kids from up and down the block come and go. On this warm spring morning, I’m meeting them for the first time at their home for brunch. They introduce me to two of their three children, all under ten. There’s a bit of pandemonium until Brittany suggests the kids go upstairs to play video games. We settle into the kitchen and Scott asks what I’d like in my omelet.

Over a quiet dinner, Scott mustered the courage to ask Brittany, “Does it ever make you sad that you’ve had your last first kiss?” Her reaction wasn’t anger or horror. Her reply was, “Yes.”

Brittany and Scott have been married for sixteen years. She was barely twenty and he was twenty-four and, like most Mormons, were virgins when they wed. They grew up in strict Mormon families and rarely questioned the traditions of the church. But out in the wider world, as they worked to build their careers—she as a nurse and he as a business owner—they became disillusioned with the teachings of the Mormon church. They were particularly disturbed by the historical celebration of polygamy, which condones men taking multiple wives but forbids the same for women. “Coercion was the nature of patriarchal Mormonism,” says Scott. And they weren’t fine with that. They moved to Washington State to be closer to Brittany’s family. Two years later they chose to leave the Mormon church.

Life was good. Their families were supportive, and they’d settled into a new housing development in Skagit County. They weren’t at all unhappy with the marriage they had. But one evening, over a quiet dinner, Scott mustered the courage to ask Brittany, “Does it ever make you sad that you’ve had your last first kiss?” Her reaction wasn’t anger or horror. Her reply was, “Yes.”

It’s estimated that over 21 percent of the US population has engaged in some form of Consensual Non-Monogamy (CNM), defined as having two or more intimate partners at the same time with the knowledge and consent of all parties. Furthermore, around 5 percent of the population identify primarily as non-monogamous, cited in the Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, and is quite possibly an underestimation. CNM is an umbrella term that encompasses a variety of relationships styles: including polyamory, swinging, and other non-exclusive intimacy (depending upon the degree to which those involved are seeking a sexual encounter or an emotional connection). It’s become a nationwide talking point, covered now in even the most mainstream publications like TIME magazine.

What does CNW look like in the Pacific Northwest? How do those who practice it find a community of others with whom to connect? Where do people go for help with navigating the tough issues that arise while attempting to be good partners and intimate friends with more than one person? And is CNM more prevalent in Cascadia than other parts of North America?

The most comprehensive list of CNM groups can be found on Facebook, where local chapters are listed by state and province, as well as countries outside the United States (US) and Canada. Though most US states now have CNM Facebook groups, there are a few, like Alabama, Arkansas, and Oklahoma, whose citizens have yet to create any. Meetup is also a good resource, listing 406 CNM groups worldwide. California far exceeds every other state in the number of groups organized around CNM. But when you look at Cascadia as a region, we’re not far behind.

Charyn Pfeuffer, who writes extensively on all matters related to sex, dating, and relationships, is a self-proclaimed drum-beater for owning your own pleasure. She grew up in Philadelphia and lived for a time in California. On a whim, she moved to Seattle after becoming smitten with a West Coast native she met on a California beach. Thought their relationship was brief, she fell in love with the relaxed feel of the Emerald City and its easy access to the outdoors. She moved away a few times but has come back with no plans to leave again. “I don’t play golf or have a trust fund, so central California isn’t really my place,” she tells me.

In Seattle, Pfeuffer socializes with a wide variety of people who are consensually non-monogamous. She feels it’s an easy city in which to be honest about being open; Seattle’s sizable art and Burning Man communities often go hand in hand with CNM. She notes, however, that Seattle still has a small pool of non-monogamous people, so you tend to run into them again and again. “It’s important to stay friends with your exes!” she advises.

Pfeuffer is active on the PNW Polyamory Facebook group where she participates in a wide variety of discussions. Like many Facebook groups, a person must have a verified Facebook account and answer a few questions in order to gain membership. Administrators approve participation and oversee strict codes of conduct regarding posts and comments. “It’s a safe place to explore love and sex and consent. Conversations that are pretty much mainstream, now. And I’m seeing more families who are coming out and raising children while being openly poly.”

We met to take a walk through Seward Park, at the southeast end of Seattle. She told me a story that illustrates her comfort in this city. “One day my boyfriend, his wife, and I rented an electric boat on Lake Union.” She went on to describe a happy time on the water with two people she loved, where their affection was openly shared. When they docked to return the boat, giggly and huggy, a conventional-looking attendant greeted them with curiosity. “Are you guys…uh…all together?”

“Yeah,” Pfeuffer replied. “This is my boyfriend, this is his wife and my girlfriend.”

“Cool!” he said, without flinching.

Pfeuffer loves seeing this kind of response. Introducing partners this way has allowed her to normalize the significance of having more than one.

This is the first time in my life I’ve had this kind of community. If I broke down on the side of the road, there’s at least a dozen people I know [through this group] who would come to my rescue.

Another woman I corresponded with, who chose to remain anonymous, because she runs a business in a small town between Seattle and Tacoma, is active in a Seattle group that has grown to over a thousand members through connections made on OKCupid. They started out as a game night gathering of self-proclaimed “nerds” and have since morphed into multiple subgroups, such as poly parents or movie lovers. She writes, “It’s not like we’re recruiting new members, they just come in as they’re invited by existing members. Once they’re invited, they’re required to attend at least one in-person event. This ensures everyone has at least a little skin in the game, and because our focus is on actual real-life events [rather than just online discussions] we hope that this will discourage contentious online interactions. It’s harder to be rude to someone online when you think you might see them at the barbecue, right?”

She doesn’t mind that the organization is rather incognito. The intent is to welcome people who are practicing non-monogamy and not simply poly-curious. “I never felt I had my own tribe,” this woman tells me when we speak by phone. “This is the first time in my life I’ve had this kind of community. If I broke down on the side of the road, there’s at least a dozen people I know [through this group] who would come to my rescue.”

It’s not hard to find people in Seattle happy to talk about polyamory, and what it means to them. One of the more interesting conversations I had was in The Re-bar during a performance of Bawdy Storytelling. Bawdy is like The Moth for kinky people. Storytellers get up on stage and tell their tales of eye-opening, sometimes transformative, experiences of unconventional adventure. There’s almost always a lot of laughter involved and a dropping of defenses after watching other people describe their vulnerable moments. One man had the crowd howling when he recounted arriving at a swinger’s party only to discover his dad and step-mom there. Another described how she became an enthusiastic practitioner of sploshing, which she hadn’t known about until a man in a grocery store asked if she’d ever consider sitting on a cake for him.

During the break, I began chatting with the hand-holding couple sitting in front of me. They both identified as polyamorous though neither had an outside lover.

“How, then is that polyamory?” I asked.

“Because,” one replied, “I simply believe in my heart that I can love multiple people. I don’t need to be having sex with them.”

“But isn’t that just love? Like I love my close friends?”

“It’s deeper than that. It’s the freedom to admit to intense feelings for other people without it being seen as bad.”

Vancouver BC, though smaller than Seattle by nearly 100,000 people, has a bit of a different story. Chelsey Blair, who grew up in Vancouver, paints a less thriving picture for those seeking CNM connections. Though not unaccepting, Blair says, “Vancouver [polyamory] isn’t really a community, it’s more of a scene.” She attributes this to the transitory nature of a city that is expensive to live in. “If you’re not relatively privileged, you can barely survive here.” She also feels the group forums that exist to discuss issues of non-monogamy are limited. “We have two main groups; VanPoly and Vancouver Poly 101. The same two dudes have been running those for as long as I’ve been here. There are women running some events, but they’re not as publicized as VanPolly and Poly 101.”

Blair, who writes on issues of queer feminism, relationship anarchy, and CNM, saw holes in the discussions around polyamory in Vancouver. Other groups, she says, “…weren’t really talking about the problems of non-monogamy. People were talking about how awesome their lives were. I wanted to talk about how it can get really fucking sticky.” Occasionally, she’ll hold discussion groups at small pubs to cover the issues she doesn’t feel the established polyamory groups are covering.

“But, the bottom line is, no matter where you are, you have to make the effort to find the connectors, she says, “I’m a connector.”

Romantic love is socially constructed. But if, as individuals, we make our choices autonomously and love the way we choose to, rather than the way we’re expected to, it doesn’t take much to alter the script.

In contrast to Blair’s outspoken efforts, Carrie Jenkins is an introvert, but in her own way she is influencing the conversation around polyamory more than most. She holds a prestigious Canada Research Chair in the philosophy department at the University of British Columbia where she’s a professor teaching courses on epistemology and metaphysics. She’s also the author of What Love Is: And What It Could Be, a book that discusses the nature of romantic love. She lives with her husband, who dates other women, and her boyfriend lives close by. Their friends and academic community know about their lifestyle. “We are open because it helps to move the conversation along when they see boring professors living this way.” She chooses not to attend CNM events or socialize in any poly-focused communities. “I just talk to my friends about it.”

In her book Jenkins, challenges us to question the way we conduct our relationships. “Romantic love is socially constructed. But if, as individuals, we make our choices autonomously and love the way we choose to, rather than the way we’re expected to, it doesn’t take much to alter the script.”

Jenkins likes to break down the standard model of traditional marriage without devaluing marriage itself. “Some people are surprised when they try non-monogamy that it’s not so terrible. If there’s enough trust [between a couple] it doesn’t mean the end of a relationship when people become intimate outside their partnerships.”

She feels Vancouver is a good place to live as non-monogamous compared to the rest of the world. In fact, she would put Vancouver near the top of the CNM-friendly list having also lived in Australia, the US, and the UK. “It’s a city where there’s a baseline of people having conversations about how to live in a thoughtful, intentional way. Once you start having those conversations you see the value in how other people are doing things. Any relationship is customized to the individuals having it. Non-monogamy forces you to do a lot of the work that is important to do anyway.”

Portland, more than Seattle or Vancouver, has more active non-monogamous communities per capita.

As far as other books on the topic, Jenkins recommends Opening Up by Tristan Taormino. She also likes The New I Do by Susan Pease Gadoua and Vicki Larson – a book that outlines many different ways to conduct a marriage, only one of which is CNM.

Jenkins agrees joining Meetup and Facebook groups that discuss open relationships is a great way to seek answers from those who have made their own mistakes. And for people seeking to date others open to CNM, OkCupid allows users to filter for matches who are open to non-monogamy.

Though Portland is the smallest of Cascadia’s big cities, most of the people I spoke with agree that the City of Roses has a reputation as the most non-monogamy-friendly place in the Pacific Northwest.

A quick discussion search on Reddit uncovered these gems:

-

-

-

-

- A friend who lives in Portland says you can’t swing a dead cat without hitting part of a [poly] triad there.

- As someone that lives in Portland, we frown on swinging dead cats because that’s not very vegan–friendly but otherwise the statement is true.

- Portland is very poly friendly… A survey by an alt weekly (particular audience, but still) had 40 percent of responders identify as non monogamous.

-

-

-

Though I couldn’t find confirmation of that last comment, the 2018 Sex Survey by the Portland Mercury reports 13 percent of respondents identify as non-monogamous whereas 38 percent say they consider themselves “monogam-ish”.

“Portland, more than Seattle or Vancouver, has more active non-monogamous communities per capita,” says John Sickler, a Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW) psychotherapist living in Portland since 2004. “In Oregon you have deeply held beliefs in the politics of personal freedom, personal expression, sexuality, and libertarianism.”

After divorcing five years ago, Sickler says he felt adrift in the dating world, reluctant to go out on a limb so soon in a relationship. However, he wasn’t very good at dating casually. He wanted to connect deeply with women, which led to finding himself in significant relationships before he was ready. He joined SexPositive Portland to improve his communication around issues of love and intimacy. That’s where he met Gabriella Cordova, executive director of Sex Positive Portland and founder of Sex Positive World.

“Gabriella didn’t want to start dating until I’d been a part of the [SPP] community longer. We thought it was going to stay casual but that changed quickly. She was involved in a long-term relationship in Los Angeles. Eventually, all our other relationships got smaller and we got bigger.”

They married in 2018 and live together with his teenagers. “We are more monogam-ish. We enjoy living together,” he says. “Although we do date some apart from each other and Gabriella continues to see her partner of 10 years in Los Angeles, we mostly enjoy dating people together.”

They are both now involved in supporting a sex-positive culture through their work, he as a psychotherapist and she as an organizer of multiple national and international CNM events. Sex Positive Portland exists to educate and explore a variety of aspects of sexuality to which a lot of people don’t have access. It runs events based on Levels 1-4 which start out as strictly social and educational. Level 2 and 3 events, Sensual and Sexy, are conducted under clear rules of conduct: consent and nurturing, sensual and sexual energy but stop short of penetrative sex or orgasm. Level 4 events are “anything goes,” according to Sickler, but require a member to be deeply involved with the SPP community and attendance is granted on a case by case basis.

Even if a person would never identify with or practice polyamory, simply attending these types of events, says Sickler, is an avenue for learning about all facets of intimacy. “It’s a safe community,” he says. “SPP educates and explores a variety of aspects of sexuality that a lot of people don’t otherwise have access to.”

It’s easier to learn from other’s mistakes. We’re finally getting a feel for what works and what doesn’t. A lot of mistakes will be made along the way if you don’t engage with a community.

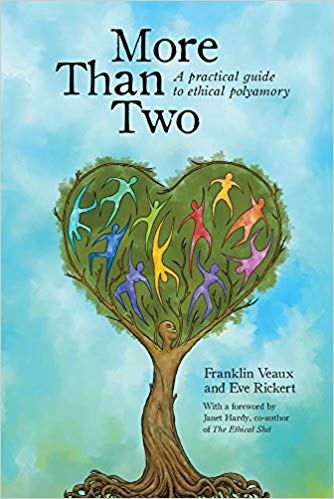

Franklin Veaux is the co-author (with Eve Rickert) of the book More Than Two: A Practical Guide to Ethical Polyamory (2014). He moved to the Portland area in 2007. As a child, Veaux heard a fairy tale about a princess forced to choose between two handsome princes, and he thought, Everyone knows princesses live in castles and castles are big enough for both princes. So why does she have to choose?

Veaux has always openly identified as non-monogamous but didn’t think there were many people who felt the way he did. When he stumbled upon a small polyamory discussion group online in 1992, he says, “The heavens opened up for me! Oh my god, there are other people like me?” Veaux, who grew up in Tampa, FL, began writing about his personal experiences and sharing his stories online. Soon, the burgeoning Poly Tampa invited him to join their group. “There were only about ten people at the first meeting. Now I’m told they regularly attract sixty to seventy.”

Veaux has always openly identified as non-monogamous but didn’t think there were many people who felt the way he did. When he stumbled upon a small polyamory discussion group online in 1992, he says, “The heavens opened up for me! Oh my god, there are other people like me?” Veaux, who grew up in Tampa, FL, began writing about his personal experiences and sharing his stories online. Soon, the burgeoning Poly Tampa invited him to join their group. “There were only about ten people at the first meeting. Now I’m told they regularly attract sixty to seventy.”

“We were told when [More Than Two] came out that it helped to show how to have functional relationships. When you’re in a poly relationship, you’re juggling multiple people’s needs and it forces you to be your best and to pay attention to your partners. Humans are all born of frailty and error.”

What Veaux sees in Oregon is an enormous diversity in the practice of polyamory. For instance, there are poly groups devoted to rhythm and dance, to families with children, and to asexual hugging. “What was interesting to me about Portland [in contrast to Tampa] is you see a whole bunch of different poly meetups every day of the week. There are many options to choose from.”

When I asked him how important community is to the practice of polyamory, Veaux said, “Very, very, very! Experience is the best teacher, but sometimes the tuition can be very high. It’s easier to learn from other’s mistakes. We’re finally getting a feel for what works and what doesn’t. A lot of mistakes will be made along the way if you don’t engage with a community.”

Some people I spoke with, especially those who have considered themselves polyamorous before anyone put a label on it, feel that where they live is not critical to how they love and don’t seek out community that identifies as CNM. Christopher Fuelling, founder of the LA/Kansas City-based Teatro Korazon, wrote to me, “In the metro areas [of Seattle, San Francisco and LA], there are lots of “poly” groups and events but it seems they’re largely a temporary support-system for people breaking out of traditional relationships and “on-ramping” into alternative lifestyles.”

Fuelling feels that ‘poly identity’ is usually abandoned as more pertinent identifiers emerge, such as his work. He’s found his career in the creative arts to be a natural environment for people open to the concept and practice of non-monogamy.

Some people who find out you’re open think it means you’re open to them having sex with you, regardless of their own relationship status. Those are the biggest assholes of all. Which is one of the reasons I’m not super “out” about it.

Still, many parts of the US are more socially conservative than the Pacific Northwest. “Twenty-five years ago, in my hometown of Muncie, Indiana, there was one gay bar, shared by all the gays and lesbians in a city of 70,000. In Kansas City, MO polyamory is still counterculture enough that there are a few poly groups, one for families and one for slightly younger folks. They meet regularly and share their stories of ‘coming out’. It’s often a harrowing experience [in the Midwest] and justification for child custody lawsuits. There is a ‘survivor’ mentality that bonds many of them here.”

Fuelling doesn’t actively participate in groups focused on CNM. “In my personal story, as I’ve been thinking, living, and writing about ‘non-monogamy’ (since the late ’80s and before ‘polyamory’ was even a word), I never felt I needed to belong to a group that identified itself as a poly community.”

A woman I met with in Bellingham agrees. “Poly is just so uninteresting to me as a topic of conversation. It just describes how I live my life, anyway. It’s not necessarily what you want or need for yourself but what you want other people in your life to have. I want them to have the freedom to have all those other connections.”

This echoes what Carrie Jenkins, the author of What Love Is, told me at the end of our conversation. “I wish one day, it wouldn’t be a big enough deal to be interviewed. That would be my ideal world.”

However, what my Bellingham acquaintance has seen in this rapidly shifting sexual climate, are erroneous assumptions about polyamory. “Some people who find out you’re open think it means you’re open to them having sex with you, regardless of their own relationship status. Those are the biggest assholes of all. Which is one of the reasons I’m not super “out” about it.”

This is echoed in a recent essay by Dedeker Winston, published in The Gottman Institute newsletter. “Nearly every polyamorous woman I know has received slut-shaming messages on dating sites that include rape threats or death threats. This level of social fallout is certainly not unique to non-monogamous people, but an unfortunate mainstay for many whose ways of loving and living do not align with mainstream values.”

After Brittany and Scott’s ‘Last First Kiss’ conversation, they felt wading into non-monogamy was flying by the seat of their pants. Brittany confessed that yes, she would really like to be kissed by her high school boyfriend again, a man she still thought about often but had never slept with. She was surprised to hear Scott’s fantasies, things that didn’t appeal to her but that she felt were experiences he deserved to explore with her support.

In the Pacific Northwest, a lot of people are coming and going, and where you’re from or where you’re headed is not much of an issue. There is a genuine ethic of acceptance here.

“I thought we were playing with fire at first,” Brittany tells me. “We had no reference point, no friends doing the same thing. It called on us to question our sense of morality. It caused us to question whether we were enough for each other. But, we opened up because we both wanted to. Had we not, I would have never faced my insecurities. We’ve learned to be compassionate and understanding of each other.”

They’ve found community through websites established for people who have left the Mormon church, some of whom are also living non-monogamous lives. That was necessary for a time. Do they feel a part of a non-monogamous community near where they live? Not particularly, though they do occasionally travel to Vancouver for socializing and are making friends through group events. Their community mostly exists within their own neighborhood. “In the Pacific Northwest,” says Scott, “a lot of people are coming and going, and where you’re from or where you’re headed is not much of an issue. There is a genuine ethic of acceptance here.”

My biggest surprise came when they told me all their neighbors know about their open marriage and it hasn’t caused any fallout. “We were one of the first families to move here, and this was several years before we opened up. People got to know who we were, and we made a lot of friends.”

There have been humorous moments, like the week Scott was away on business and a neighbor spotted a strange car in the driveway.

“She called me to tell me my wife might be having an affair. When I told her I knew and that I was acquainted with her visitor, we both had a laugh.”

What Brittany and Scott want for their marriage is what a lot of us probably want; good parenting and a solid foundation without sacrificing intimacy with each other. But what they wanted for themselves as individuals sometimes differed. As they began to seek out ways to fulfill their interests they grappled with the inevitable sticky issues.

“When you deal with jealousy, it creates a lot of self-awareness. When I do the work myself, I feel that jealousy a lot less,” says Brittany. “When Scott fell in love [with another woman] it was slightly threatening. But I know where his priorities lie.”

As I struggle to transcribe all the pearls of wisdom coming from this woman, I realize I’ve veered off the topic of polyamory in the Pacific Northwest. But Brittany embodies what I’m familiar with as a career woman and a mother, living an outwardly conventional life. Those of us who feel troubled by the mere concept of non-monogamy might be more receptive to its stories when they are told by the person who picks up your kids after school.

“I like having both worlds,” she says. “I want to create an environment that allows [my partner] to thrive. Not just as a husband and father, but as an individual. I ask myself often, ‘What can I do to give you freedom?’ We don’t go easy into vulnerability, but I’d rather be proactive in my relationships. Having grace and compassion for each other has been our savior. I don’t ask [Scott] to do anything about my jealousy, I just let him know about it.”

Scott chimes in, “The times I’ve felt jealous were the times I wasn’t taking care of myself.”

“I like having both worlds. I’m so fucking lucky!” says Brittany. “At the end of the day I’m so glad we’ve been on this road.”

As I wrap up this article, I take a drive with the building contractor in charge of my house remodel. Perhaps the strongest indication of a shift in how we view sexuality in our region didn’t come from any data I found, or interviews I conducted, but from this politically conservative, libertarian man as we rode through Whatcom County in his F350 pickup. I was telling him about this article. We agreed that, despite how bad things seem in the world, very much of life is probably better now than it ever has been, especially for people who were once marginalized. “So much has changed in only a few decades,” he says. “It’s not like we just tolerate gay people or trans people. We accept them for who they are. None of the guys I hang out with make jokes about it now.”

“So, do you suppose polyamory might become the same No Big Deal?” I asked him. He chuckled and squirmed a little. “Well, I don’t think I could do it. I think it’s a fantasy for a lot of guys. My life is so much better with my wife [in it]. I don’t want to mess with that.”

“Sure,” I said, “that works for you. But the people next door?”

“They can do whatever the hell they want.”

Editor’s note (Sept. 13, 2019): It has come to our attention that there is a controversy in the polyamory community about author Franklin Veaux’s conduct in multiple past relationships. If you are seeking support as one of those people involved, or if you would like more information, find out more at this link. Franklin Veaux is not responding to the allegations at this time.

Photo credits: Top banner: Scott and Brittany by Alvin Crain, Chelsey Blair and Carrie Jenkins by Jackie Dives. John Sickler & Gabriella Cordova by Thomas Teal. In the article: Charyn Pfeuffer by Nia Martin. Chelsey Blair and Carrie Jenkins by Jackie Dives. John Sickler & Gabriella Cordova by Thomas Teal.

Karin Jones is an editor who lives in Bellingham, WA and is a columnist for the UK’s Erotic Review Magazine where she writes about all things sex and relationships. She’s had work published in the New York Times, Huff Post, The Times of London, and the Sydney Daily Telegraph. E-mail her at relationships@ermagazine.org and follow her on Twitter at @mskarinjones.

Alvin Crain is an enthusiastic people-centered family and wedding photographer who is committed to capturing stories in a fun, lighthearted way. E-mail him at alvin@alvincrainphotography.com and follow him on Instagram at @alvincrainphotography.

Jackie Dives explores themes of identity and womanhood through the medium of digital and analog photography. Her work has been published internationally in publications that include Canadian Geographic, The Tyee, VICE, The Globe and Mail, and Maclean’s. She lives and works in Vancouver. Follow her on Instagram at @jackiedivesphoto.

Nia Martin is a Seattle-based photographer, writer and editor. Her work has appeared in both print and online publications including The Seattle Times, Seattle magazine, Bitterroot Magazine, The Fold magazine and Real Change, among others. Follow her on Instagram at @niatakesphotos.

If you appreciate great journalism like this on issues that matter in the Pacific Northwest, please become a supporting reader of Cascadia Magazine. We can’t continue to publish great writing like this without your support. Become a recurring contributor or give a one-time donation at our donate page. Thanks!