Holding the US Navy accountable for dumping toxic copper into Puget Sound

This investigative feature on pollution by the US Navy in Puget Sound was made possible by a generous grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Barnacles have been a drag on ships since ancient times. Now their removal is the root cause of what is Washington state’s biggest environment-oriented legal action against the US Navy’s Puget Sound Naval Shipyard (PSNS).

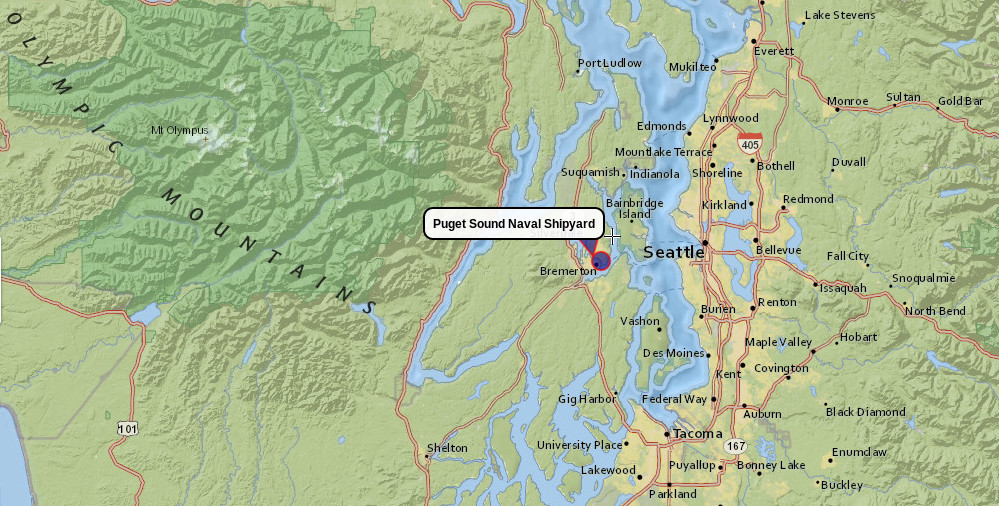

The lawsuit regards the “anti-fouling” paint used on hulls of aircraft carriers to remove barnacles. Copper, the key ingredient, threatens the fish and sealife of Puget Sound and the Salish Sea. The Navy has scraped, or is expected to scrape, copper-laced paint off carriers at PSNS in Bremerton, Washington.

The aircraft carriers in question are the USS Independence and the USS Kitty Hawk. The USS Independence has spent 19 years at the Naval Inactive Ship Maintenance Facility—a dry dock for retired US Navy vessels at PSNS on Sinclair Inlet south of Bremerton. The decommissioned USS Kitty Hawk has been at the same dockyard since 2009. The two ships were commissioned in 1959 and 1961, respectively.

From January 6 to 27, 2017, the Navy scraped up to 700 cubic yards (the equivalent of 70 dump truckloads) of debris from the hull of the USS Independence into the water. An unknown fraction of that material consists of copper-laced paint chips—enough to raise the concentration of copper above permissible levels. The debris and chips still sit on the bottom of the inlet, and critics fear that the Navy will do the same with the former USS Kitty Hawk at the same spot. The Washington State Ecology department claims that this is one of the worst incidents of pollution by the Navy at PSNS, which until now has been cited for occasional minor violations on discharges from the shipyard’s sewage treatment plant.

We did this because it was such an egregious violation. The [Navy’s Bremerton] shipyard is one of the highest sources of copper in the Puget Sound region. This has a huge potential to pollute.

It’s not the first time that an aircraft carrier cleanup at PSNS has attracted the attention of state environmental regulators, however. In 2012, the aircraft carrier USS Reagan was docked for several months at Bremerton after being exposed to offshore radioactive plumes from the reactor meltdown in the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Fukushima, Japan. However, the radioactive substances in that plume mostly consisted of Iodine 131, which has a half-life of eight days. According to Earl Fordham, deputy director of the Office of Radiation Protection at the Washington Department of Health, the USS Reagan’s radioactivity had completely decayed by the time it docked at Bremerton.

In June 2017, a lawsuit was filed in federal court by Puget Soundkeeper Alliance and Washington Environment Council (WEC)—two Seattle-based non-profit environmental organizations—and the Suquamish tribe located on the Kitsap Peninsula. The lawsuit seeks to force the Navy to remove the debris scraped from the USS Independence that now sits on the seafloor, and to prevent future violations by the Navy. The planned scraping of the USS Kitty Hawk is of critical concern.

“We did this because it was such an egregious violation,” said Mindy Roberts, Puget Sound program director for the Washington Environmental Council. “The [Navy’s Bremerton] shipyard is one of the highest sources of copper in the Puget Sound region. This has a huge potential to pollute.”

Leonard Forsman, Chairman of the Suquamish Tribe, noted that the effects on the Salish Sea from the Navy’s activity are cumulative. “When the water quality gets worse, you affect the ecosystem. You affect the orcas and the salmon.”

The Navy declined to comment about the issue to Cascadia Magazine.

However, it has sought to dismiss the lawsuit on the grounds that the work on the USS Independence is already finished, and it is unknown if and when the USS Kitty Hawk’s hull might be scraped at Bremerton.

Bill Sherman, an assistant attorney general for Washington and chief counsel for the AG office’s Environmental Protection Unit, countered that the paint scrapings from the USS Independence are still on the bottom of Sinclair Inlet, and still polluting Puget Sound. “It’s an ongoing discharge,” Sherman said, noting that tidal currents stir up the debris and continue to leach copper into the Sound.

In addition to having the Navy clean up the chips from the USS Independence, the litigation is supposed to prevent the Navy from taking the same scraping approach to the USS Kitty Hawk in the future, he said.

The Washington Attorney General’s Office joined the lawsuit as a co-plaintiff in April 2019. The state received a Navy-contracted report in October 2018 that showed excessive amounts of copper remain on the inlet’s floor below where the USS Independence was docked, Sherman said.

The lawsuit seeks a judgment that federal and state clean water laws have been violated; requests that the Navy stop additional violations; and demands that the plaintiffs receive ongoing updates of when the Navy plans to clean and scrape vessel hulls at Bremerton.

This litigation’s origin can be traced to barnacles.

Barnacles are tiny crustaceans, related to crabs and lobsters, that exist in huge clumps as a survival technique. If predators attack a clump to eat them, the large numbers ensure survival. They live in shallow and tidal waters, attaching themselves to solid surfaces, such as the hulls of ships and boats. Barnacles have glands that secrete a cement-like glue with an adhesive strength of 22 to 60 pounds per square inch.

Bottom line: They’re really hard to scrape off.

According to a 2009 statement by the Navy, which studied barnacles’ effects on its ships, an infestation of barnacles can reduce a ship’s speed by 10 percent and increase an barnacle-encrusted vessel’s fuel consumption by up to 40 percent to counteract the drag. This translates to an extra $1 billion in fuel costs per year and a significant increase in carbon emissions for the Navy.

Prior to the creation of steel hulls, copper sheathing was installed on wooden ships to fight barnacles. Copper in paint is poison to barnacles, which has led to widespread application of copper oxide as an anti-fouling paint on the hulls of naval and civilian vessels.

Copper is a finicky element in nature. Living things from fish to humans need ultra-small doses of copper. But higher concentrations of copper can be toxic, and the element does not break down into less-toxic components.

A 2012 Nature Conservancy report on copper and Alaskan fish said copper “is one of the most toxic elements to aquatic species, at levels just above that needed for growth and reproduction it can accumulate and cause irreversible harm to some species. Copper is acutely toxic (lethal) to freshwater fish via their gills in soft water at concentrations ranging from 10-20 (parts per billion).”

Copper can greatly reduce a fish’s sense of smell, damage neurons that help it stay aware of its environment, reduce growth, cut back on resistance to diseases, disrupt internal organ function, change blood and enzyme chemistry, and disrupt migratory patterns.

Roberts, of the Washington Environment Council, used to be a Puget Sound pollution expert for the Washington Department of Ecology. Her expertise included Sinclair Inlet, which includes the Navy docks on PSNS’s south side, and Dyes Inlet, which cuts through eastern Bremerton and extends north of the city to Silverdale.

In a January 2018 affidavit accompanying the lawsuit, Roberts cited a 2003 Navy study that 23 percent of the copper in Sinclair and Dyes Inlets came from Navy ships, 25 percent came from private vessels, 16 percent came from commercial hulls, 7 percent came from the Navy’s drydock facilities, and the rest from other sources. Of the Navy-originated copper, 68 percent accumulated in Sinclair Inlet sediments and the rest drifted into central Puget Sound.

When the 1,070-foot, 60,000-ton USS Independence was decommissioned in Bremerton in 1998, it legally ceased to be a vessel. Instead, it became a “floating craft.” The same is true with the decommissioned USS Kitty Hawk. This means the two ships are governed by the federal Clean Water Act and state water quality laws. Active Navy ships are largely exempt from those laws.

In 2016, the Navy decided to send the USS Independence to International Shipbreaking in Brownsville, Texas. There the carrier would be torn apart, with the scrap metal going to Mexico, and the armor plating going to build new naval ships in Pennsylvania. But the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) issued an environmental recommendation (that the Navy honored) that the USS Independence, with ample marine growth on its hull, not be allowed to transport invasive species into the Brownsville facility in 2016, according to Roberts.

Roberts examined a 2016 briefing by the Navy to the Suquamish tribe and found that the feds estimated 284 to 620 tons of barnacles and other organisms were expected to be scraped off the USS Independence. Another 2016 Navy report cited in Roberts’ affidavit indicated that Chinook salmon, coho and chum could be present in Sinclair Inlet when the hull of the USS Independence was to be scraped.

”It is well-established that dissolved copper adversely affects salmonids, even at very low concentrations,” Roberts said in the affidavit.

That fact brought the Suquamish tribe into the lawsuit. In 1855, the Suquamish—who have lived for millennia on the shores of Puget Sound —signed the Treaty of Point Elliott with the United States, giving up most of their ancestral lands in return for retaining the right to fish, hunt, and gather in their ancestral lands and marine waters of Puget Sound, including Sinclair Inlet. To protect these rights (which are contingent on water quality), Suquamish Chairman Forsman said this is the reason his tribe is fighting copper pollution tied to the scraping of naval vessels

In 2016 the Navy concluded that any hull paint released by scraping with various brushes and underwater jets would not harm marine life in Sinclair Inlet. On the contrary, however, Roberts’ 2018 affidavit said she could not find a basis for the Navy’s conclusion.

The Navy consulted with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), which went on to make recommendations for mitigating measures. Roberts read a September 2016 letter from the Navy to the NFMS that declined recommendations to put an underwater silt curtain around the USS Independence during the scraping and to dredge out the accumulated debris below the carrier.

After the scraping, the USS Independence was towed 16,000 miles around the southern tip of South America and back north to Brownsville from March 11 to June 2, 2017.

“It sat in Sinclair Inlet for 19 years, where the job could have been done properly [during the previous two decades],” Roberts said.

The Navy ignored [the state’s] concerns and repeatedly downplayed the potential impact, assuring federal, state, and tribal regulatory agencies that impacts from the hull cleaning would be minimal. The Navy’s assurances are wrong.

Meanwhile, the state ecology department and attorney general’s office watched closely from the sidelines.

In late 2016 the Navy hired a consultant to measure the concentrations of copper and other substances before the scraping and then after the USS Independence was towed out of Sinclair Inlet. The copper-related studies measured sediment at six different locations beneath the USS Independence.

Although dated April 2018, the Navy did not provide the report to the state and the lawsuit plaintiffs until October 2018. The state had been seeking a report on the study since mid-2017.

That study found that one of the six locations where the USS Independence had been moored had a copper reading four times the amount that was recorded prior to the scraping. Two locations had approximately twice as much copper after the scraping than they had prior to the removal. Two locations recorded slightly elevated concentrations of copper after the scraping. And one had almost half of the initial concentration afterward.

“The thing that made the enormous difference [in deciding to join the lawsuit] was the sediment report,” Sherman said. “It was really alarming to us. It confirmed to us that this activity had no place in Sinclair Inlet.”

The state’s March 2017 court filing said: “The Navy ignored [the state’s] concerns and repeatedly downplayed the potential impact, assuring federal, state, and tribal regulatory agencies that impacts from the hull cleaning would be minimal. The Navy’s assurances are wrong.” The sediment measurements were in excess of what Washington’s regulations allow, the filing stated.

The state, WEC, Puget Soundkeeper, and the Suquamish tribe are now eyeing the 1,068-foot, 61,000-ton USS Kitty Hawk, moored near where the USS Independence used to be.

The plaintiffs expect the Navy to scrape the US Kitty Hawk’s hull in Bremerton, and worry that the Navy might again ignore state and federal clean water laws in regard to copper pollution.

The original 2017 lawsuit claimed: “Like the USS Independence, the Navy is likely to prepare other decommissioned ships at the Naval Inactive Ship Maintenance Facility for towing to a dismantling location in a manner similar to that of the former USS Independence. This preparation is likely to include in-water and continual hull scraping that will likely result in on-going and repeated un-permitted discharges of pollutants into Sinclair Inlet.”

The Navy currently has only three inactive ship maintenance facilities: Philadelphia, Pearl Harbor, and PSNS in Bremerton. This means Bremerton can expect a steady stream of decommissioned ships at its facility.

“Puget Sound [Naval Shipyard] is liable to get aircraft carrier after aircraft carrier,” Roberts said.

Photo credits: all photos are by Nia Martin. Top banner images: the decommissioned USS Kitty Hawk docked in Sinclair Inlet; Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Washington; and the hull of the USS Kitty Hawk, which the US Navy plans to scrape in future.

.

John Stang is a freelance reporter and former longtime newspaper reporter with 37 years of experience, mostly in the Pacific Northwest. Follow him on Twitter at @johnstang_8.

Nia Martin is a Seattle-based photographer, writer and editor. Her work has appeared in both print and online publications including The Seattle Times, Seattle magazine, Bitterroot Magazine, The Fold magazine and Real Change, among others. Follow her on Instagram at @niatakesphotos.

If you appreciate great journalism like this, please consider becoming a supporting reader of Cascadia Magazine. Your recurring donations helps us continue to publish quality writing on issues that matter in the Pacific Northwest. Visit our donate page to make a contribution.