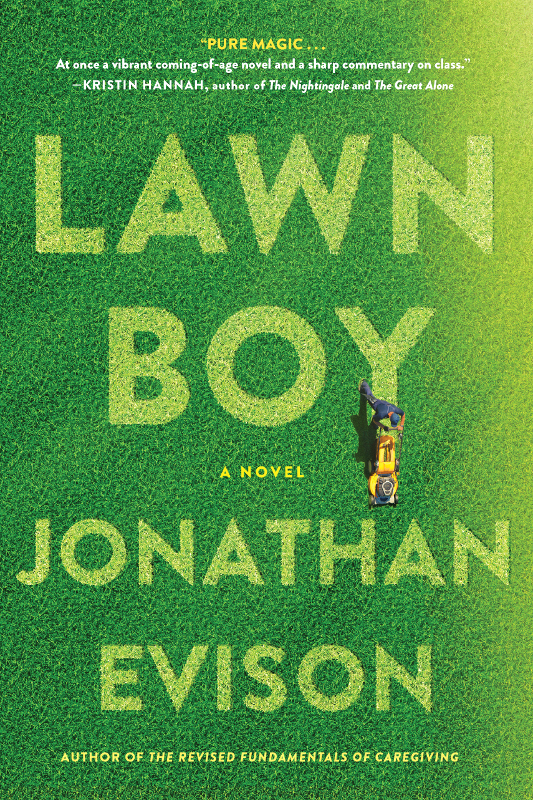

Book Review: Lawn Boy

By Jonathan Evison

(Algonquin, 312 pp., $26.95)

The first sentence of Jonathan Evison’s dandy new novel, Lawn Boy, tells you almost everything you need to know about its narrator’s background and the obstacles he’s up against.

“When I was five years old,” Mike Muñoz recalls, “back when my old man was still sort of around, I watched a promotional video for Disneyland that my mom got in the free box of VHS tapes at the library.”

No money, a broken family, a dream unlikely to be fulfilled – they’re all in that opening line, placing you casually in the heart of Mike’s world. As Mike fills in more details, it grows clearer how high the odds are stacked against him. But it’s also clear that he might be saved by two passions.

The first is for books. (“The library was the most stable thing in our lives,” he says.) The second is garden care, especially topiary, spurred by the “fastidious landscaping” of Disneyland.

Still, the obstacles he faces are formidable. At 22, he has no college degree. He lives with his mother, a waitress working double shifts to scrape by. When he loses a lawncare job he likes, he becomes erratically employed. Almost every evening he’s saddled with the care of his “developmentally disabled” brother Nate, whom he describes as “a three-hundred pound toddler.”

“I feel like I’m nothing more than what everybody needs me to be,” he says.

Mike, it’s obvious, has a good heart, even if his anger sometimes get the best of him. He’s keenly aware that people who look down on him can’t see him for what he is. He has intelligence and ambition, but those may not be enough.

“All I needed,” he believes, “was the opportunity to think beyond sustenance long enough to dream.”

Evison leaves you in real doubt whether that opportunity will ever come his way.

Lawn Boy is more tough-minded than Evison’s earlier novels (All About Lulu, The Revised Fundamentals of Caregiving, This Is Your Life, Harriet Chance!). It’s a swift, engaging read, with an alternately wry and wistful sense of humor. But it also addresses painful territory head-on, especially when it comes to American economic and cultural inequality.

In an eloquent personal essay sent out to reviewers with the book, Evison recalls his own “perpetually broke” boyhood and young adulthood, including two decades spent in odd jobs (“gas-meter-checker, auto detailer, caregiver, sorter of rotten tomatoes, telemarketer of sunglasses”) before he found success as a novelist. Of those jobs, his favorite was landscaping. Its only downside, he recalls, was clients who treated him “not as a professional tradesperson but as their personal lackey.”

Those experiences made him want to write a novel about “wealth disparity and class … a book that highlighted the myriad indignities, vagaries, and obstacles of poverty in America in the twenty-first century.”

In Lawn Boy, he pulls it off. The setting and characters couldn’t be more vivid. Mike, a self-described “tenth-generation peasant with a Mexican last name,” lives with his family in Suquamish. But most of his jobs are across Agate Passage on Bainbridge Island.

“We call the bridge the service entrance,” he quips, “because virtually nobody on the island, as far as I can tell, mows their own lawn or maintains their own pool or cleans their own gutters.”

He knows what it’s like to have no money to fix your truck when it breaks down. He knows what it’s like to live in your car for a month when the landlord raises the rent. (“I wish I could tell you it was an adventure, at least for the first few days, but it wasn’t. The experience was terrifying from the start.”)

Mike’s world consists of his near-unmanageable brother, his kind but stretched-to-breaking-point mother, and an eccentric African-American, Freddy, who moves in with them to help with the rent. There’s also a prospective girlfriend in the picture and a librarian who helps steer Mike toward novels he might like. Finally, there’s his longtime best friend whose “habitual bigotry” is increasingly getting on his nerves for reasons he can’t fully articulate.

Mike pre-empts certain questions he knows may arise in his readers’ minds. About his mother’s cigarette habit and its drain on her meager household budget, he puts things in perspective.

“For starters, she’s perpetually tired,” he says. “She’s been working fifty-hour weeks for as long as I can remember. And there’s a good chance she’s clinically depressed. Smoking gets her through that second shift. It relaxes her when the pressure is mounting. It gives her something to look forward to during her break and after work, and before work, and when she wakes up in the morning. It makes her heart beat faster. At ten bucks a day, that’s a bargain.”

While he extends a similar sympathy toward most of the people in his life, he can be harsh on himself. “I don’t really know how to think big,” he admits. He sees how the odds are stacked against him (“The thing about never having any money your whole life is that you have no way of learning about money”), but he can’t see how to fix it. His vague ideas for writing a “Great American Landscaping Novel” haven’t gotten beyond a handful of pages. His sense of self-defeat seems insurmountable: “Accept the worst like it’s inevitable. It’s easier than changing the game, isn’t it?”

It’s a sign of how well-drawn Mike’s struggles are that you want to jump into the book and help point him in the right direction. Evison eventually gives Mike a happy ending on two thoroughly unexpected fronts. If they feel a little rigged, that’s forgivable.

He’s only twenty-two, after all. He has a whole lifetime for his luck to turn again, the way it can turn on anyone trying to gain a toehold in an unforgiving world.

Novelist Michael Upchurch (Passive Intruder) is the former Seattle Times book critic. Visit him at www.michaelupchurchauthor.com.

AUTHOR APPEARANCES:

April 2: Eagle Harbor Book Co., Bainbridge Island, 6:30 p.m.

April 10: University Bookstore, Seattle, 7 p.m. (www.ubookstore.com)

April 11: w/ Willy Vlautin at Heiner Center, Whatcom Community College, Bellingham, 6:30 p.m.

April 12: Powell’s City of Books, Portland, 7:30 p.m.

April 25: Third Place Books, Lake Forest Park, 7 p.m.

April 26: Elliott Bay Book Co., Seattle, 7 p.m.

May 3: Island Books, Mercer Island, 6:30 p.m.

If you found this review interesting and informative, please consider taking a moment to joining the readers who provide financial support to Cascadia Magazine. We’re a reader-supported, non-profit publication dedicated to great writing from the Pacific Northwest. If you’re already a supporting member, thank you!